When people talk about the “Golden Age of Flying,” they often picture Pan Am.

The name alone brings back memories of sleek uniforms, glamorous jet-setting, and a time when air travel felt like a special occasion.

But behind the polished smiles and stylish hats, there were real people working hard, making history, and navigating a world that was rapidly changing.

Dr. Sheila Nutt was one of those people.

In 1969, at just 20 years old, Sheila Nutt stepped into a world that most Americans—especially African American women—had never experienced: the global skies.

As one of the first Black flight attendants for Pan Am, she didn’t just serve passengers; she challenged norms, broke barriers, and helped change the face of aviation.

This is what it was really like to be a Pan Am stewardess in the 1970s—through the eyes of someone who lived it.

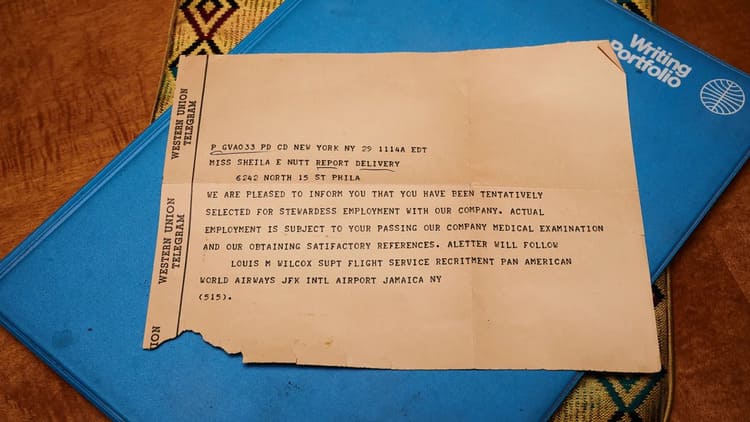

Getting the Job: Not Just About a Pretty Smile

Sheila Nutt wasn’t just randomly picked out of a crowd.

She had poise, grace, intelligence, and experience with being judged—literally.

She was the first African American woman to become runner-up in the Miss Philadelphia pageant. During that experience, she met another contestant who mentioned the airlines were hiring.

At the time, many young women were expected to become nurses or teachers.

But Sheila wanted more. So when she saw a Pan Am job ad in the newspaper, she jumped at the opportunity.

But this was no ordinary job interview.

Applicants had to meet strict requirements: a college education, a second language, specific height and weight, perfect grooming, and no eyeglasses. Despite all that, Sheila stood out.

She remembers being one of only two Black women in the crowded Philadelphia hotel lobby waiting to be interviewed.

The moment she saw those colorful Pan Am brochures with pictures of Rome, Paris, and Buenos Aires, she knew she wanted in.

“I really want this job,” she thought.

And she got it.

Training for Takeoff

Training school took place in Miami and lasted a month.

Sheila flew First Class from Philadelphia to Puerto Rico and then to Miami, her first taste of what the jet-set lifestyle could be.

In class, she was the only Black woman.

Many of her classmates had never even met an African American person before.

But Sheila stood tall.

She was elected valedictorian of her training class. Even now, over 50 years later, she remains in touch with some of those women.

The training was no joke.

Recruits learned about everything from food and wine pairings to safety procedures and emergency evacuations.

The airline wanted you to know not just how to serve a four-course meal at 35,000 feet, but how to handle real crises if they happened.

“We became connoisseurs of wines,” Sheila recalls, along with mastering grooming standards and practicing diplomacy in multiple languages.

Flying While Black

Sheila started flying out of Miami in 1970.

It was the beginning of a new chapter—for her and for the airline industry.

As glamorous as the job appeared, it came with serious challenges.

Renting an apartment with her white roommates was difficult in racially segregated Miami. Landlords were hesitant to rent to a Black woman.

In the air, some passengers were stunned to see a Black stewardess. On international flights, people often didn’t believe she was American.

Some were even openly disrespectful. Sheila recalls an incident with a South African passenger who refused to speak to her—but later apologized to her white colleagues, saying he didn’t have the “capacity” to say it to her face.

Her response? Keep doing the job with grace and excellence.

And then there was the hair. At the time, the Afro was not just a hairstyle—it was a political statement.

Sheila wore hers proudly under her pillbox hat, a quiet form of protest that still passed Pan Am’s strict appearance standards.

Life in the Skies

Despite the challenges, there were countless joys.

Sheila became a purser just six months into the job and later served as a stewardess manager.

She flew on the legendary Boeing 747, Pan Am’s crown jewel, which carried over 400 people.

Her routes included Rome, Nairobi, and other far-flung places she had only read about in school.

Layovers meant staying in top-tier hotels like the InterContinental in Nairobi—also owned by Pan Am.

In First Class, flight attendants cooked gourmet meals mid-flight and served them on china. Roast beef, steak, fine wines—it was a far cry from today’s airline meals.

Sheila took pride in being what she called a “de facto ambassador of America.” When people boarded a Pan Am flight, they saw her. They saw excellence.

A Changing Industry

But the aviation world was changing.

In 1978, the Airline Deregulation Act transformed the industry.

The focus shifted from luxury and service to efficiency and low-cost competition. Glamour gave way to budget airlines. Union jobs like Sheila’s became harder to sustain.

“It was the end of an era,” Sheila says.

Where once a flight attendant might care for a baby mid-flight or serve five-star meals, the new model was about moving people from point A to point B as quickly and cheaply as possible.

It was no longer the job it once was.

Life After Pan Am

Sheila didn’t stay in the skies forever.

When she started feeling like she had outgrown the job, she moved on. But she didn’t stop soaring.

She earned a Doctorate in Education from Boston University, writing her dissertation on occupational stress among flight attendants.

Later, she earned a Master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School.

For years, she worked as the Director of Educational Outreach Programs at Harvard Medical School, promoting diversity and inclusion—values she had lived her whole life.

Sheila also started a podcast called Sheila ‘N her Fab Friends dedicated to sharing the stories of Black flight attendants from the golden era.

“I felt it was important for our stories to be saved, to be highlighted, to be respected and acknowledged,” she says.

The Legacy Lives On

Today, Sheila Nutt is retired, happily married, and has traveled the world—including finally visiting China, a dream destination that wasn’t open during her flying years.

She still loves to fly, but she sees how different things are today.

“Back in the day, there was the image of glamour,” she says. “Now, it’s about getting from point A to point B and handling emergencies.”

But for those who lived it—and for those who hear her story now—that golden age still shines brightly.

Pan Am may be gone, but its legacy, and the people like Sheila who helped shape it, will never be forgotten.

I started to work for TWA just at the same time. Of course there was competition but just like PanAm we were proud to be with TWA. I do not recall any afro american girls that early (1970) but this has changed later on of course. And yes, it was glamerous.

Over 40 years as a flight attendant…I still enjoy it and try to throw a little of the past in my work…Thank you Sheila

I remember Sheila and flew with her a few times..she was lovely, educated and very classy…we didn’t care much about the color of your skin, we loved one another regardless of it..we loved one another for the value of the person..we still do and try to keep in touch with one another and have been pretty successful….while working for Pan Am, we considered ourselves very special..and we were..we spoke different languages..some two or three and one of us spoke twelve.

This is a lovely story about Sheila.. she would have been successful in any chosen vocation she wanted to pursue 🤵🏻♀️

hello Sheila,

It’s so good to see you here and I look forward to speaking with you soon

A big hug, Johanna

Hey Sheila! You did well! Love you story,even if you embellished a bit! ( Our class never had a valedictorian) You deserve to be proud of your many accomplishments!!

You are a wonderful testimony to what that great era was like and a real shift from its sad loss today in the airline industry.

What a great article! I’ve been flying business jets for past 20 years and love it. Aviation as Dr. Nutt experienced is still alive although not as accessible. Thanks for sharing this story!

Hi Sheila. I am Marika’s szalai bornstein. I do not remember that I ever flew with you but I love your story how you concurred everything and how high you are now without being 30 – 40 000 feet high. I was highered 11/12/1067 based in Seattle and than JFK until 2013. If you are living around NY, area would love to meet you, and if you are still interested we could Chet about the wonderful years of our life. Thank you marika szalai bornstein. ✈️